Writers, and the books they write, have always been like friends to me.

Sometimes close friends.

It is an intimate thing – to listen, imagine and yes, converse – for hours and hours – sometimes weeks and weeks – days and days.

Imagine talking on the phone for that long. It’s a long time to live in another person’s world.

Books, also, have great depth. They take time, attention. Unlike the shallow, schizophrenic world of television and other media that tells you what to think and hear and see as you sit in a passive trance – bombarding you with music, underlining each action with sound effects and laugh tracks, preempting any effort on your part besides dazed acceptance – reading a book requires a meeting of imaginations – a very vibrant act.

The author imagines and presents the world he or she imagines, and invites you to step into it and join him or her in the exploration. The rest is up to you, the reader.

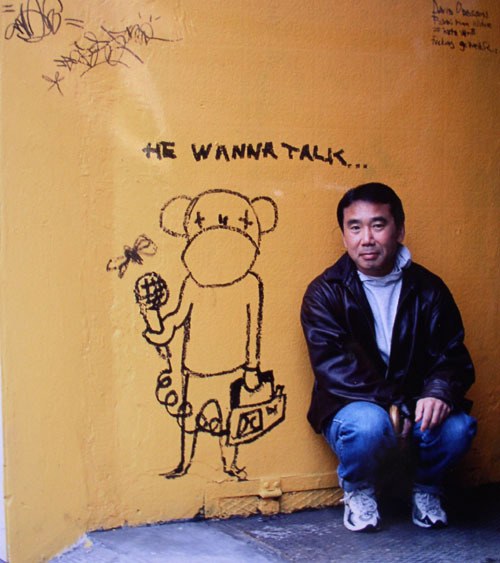

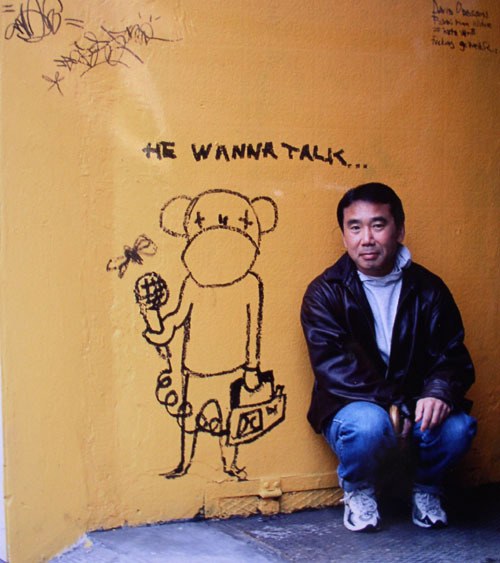

If this is so, then Haruki Murakami must be one of my best friends.

Again and again, he offers the belief that a person like him must be hard to like; that people like him are so stubborn, so different and so unexceptional – or inward, or somewhat un-social – that no one would easily be attracted to him, or them.

Perhaps this is precisely why I like him.

Mainly, however, when I read his books I feel like I am talking to a good friend, an old friend who is always interesting, who always has peculiar insights and poetic ways to express them, who feels deeply and completely the mystery of life. His companionship is easygoing and comradely, though we delve at times into difficult or frightening themes. Reading Murakami, to me, is a little like having an intense, meandering conversation in a dream that goes on and on and makes perfect sense when you are asleep but merges with your consciousness so that when you wake up you don’t doubt a thing.

In this casual wonderful memoir there were certain what Murakami calls “life lessons” that he learned or observations that he made which I find particularly relevant to my own life. For instance, there is the strong vein of what other people believed he should or could do, and what he wanted to and ultimately, did. Whatever Murakami set out to do – open a jazz bar, become a full-time writer, close the jazz bar – people opposed his actions strongly. Being Murakami, he went ahead on his own anyway.

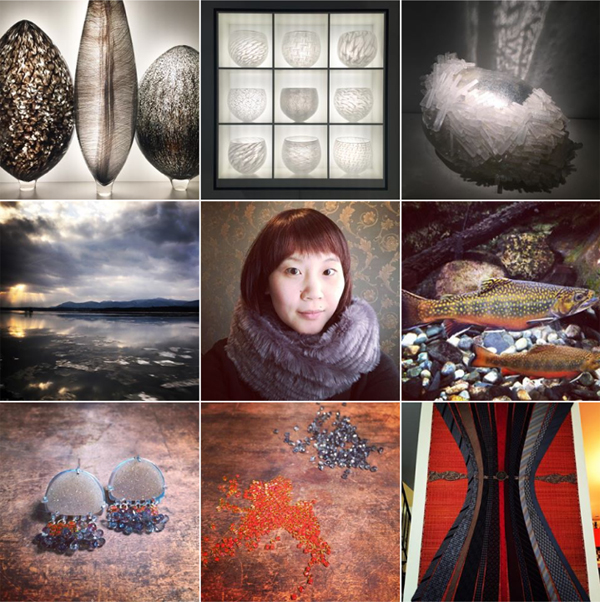

This reminds me of my experience on giving up the academic world, giving up the corporate path, giving up “success” as success – to work with my hands, to own my own business, to become an artist.

The whole society – and certainly members of my family – and friends – and random people on the street – all opposed this move. My father, a company man, couldn’t understand how I could possibly make a living. Becoming a professor or professional white collar worker was his idea of procuring a steady and successful living for oneself. It is what he did, and did well. Friends and acquaintances looked upon my work and my endeavors with incomprehension. Society, at first, was no different. “Starving artists” were rampant, according to the word on the street. I really had to dig to find examples of successful artists, metalsmiths, colleagues.

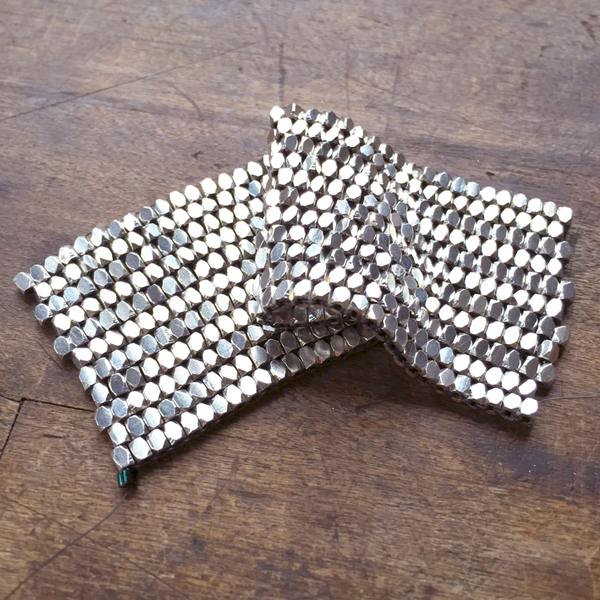

I also felt a sort of inferiority about not studying metalwork in school. With a degree in literature and only a few art classes under my belt, I started my real metalworking apprenticeship in Western China, Nepal, Tibet. I have taken some excellent classes, but I have never worked under a master and never completed any degrees. I am mostly self-taught, and without the luxury of time and resources to explore this new medium that students take for granted (and inheriting the respect for education my family and culture instilled in me) as well as the technical know-how years of study can impart I always felt a little behind the times.

Murakami writes:

I never disliked long-distance running. When I was at school I never much cared for gym class, and always hated Sports Day. This was because these were forced on me from above. I never could stand being forced to do something I didn’t want to do at a time I didn’t want to do it. Whenever I was able to do something I liked to do, though, when I wanted to do it, and the way I wanted to do it, I’d give it everything I had.

This is how I feel about my metalwork.

I’m giving it everything I have.

Murakami also speaks of closing his jazz bar and taking up full-time writing and changing his and his wife’s lives and schedules. Getting up early, going to bed early. Only seeing people they wanted to see. Going from a more open life of welcoming any and all customers – to a more closed life, of getting by more privately. And how some people also couldn’t understand this and even got mad at him.

Running your own business is damn tough and dealing with people is probably the toughest part of it. I’ve often torn my hair out negotiating custom work, or politely receiving rude, insensitive treatment, or introducing my work to a dismissive or indifferent crowd, so I know what it is like to deliberate over how to present oneself. I can be quite charming in my outward moments, but I am, like Murakami, essentially a person who “doesn’t find it painful to be alone. ” I enjoy it. That’s why I can spend hours and hours at my workshop, playing and working away.

So working with people as an artist and business owner is a worthwhile challenge, and it was nice to hear from Murakami his take on the matter.

In his words:

I’m struck by how, except when you’re young, you really need to prioritize in life, figuring out in what order you should divide up your time and energy. If you don’t get that sort of system set by a certain age, you’ll lack focus and your life will be out of balance. I placed the highest priority on the sort of life that lets me focus on writing, not all the people around me. I felt that the indispensable relationship I should build in my life was not with a specific person, but with an unspecified number of readers. As long as I got my day-to-day life set so that each work was an improvement over the last, then many of my readers would welcome whatever life I chose for myself. Shouldn’t this be my duty as a novelist, and my top priority? . . .

In other words, you can’t please everybody.

Even when I ran my bar I followed the same policy. A lot of customers came to the bar. If one out of ten enjoyed the place and said he’d come again, that was enough. If one out of ten was a repeat customer, then the business would survive. To put it the other way, it didn’t matter if nine out of ten didn’t like my bar. This realization lifted a weight off my shoulders. Still, I had to make sure that the one person who did like the place really liked it. In order to make sure he did, I had to make my philosophy and stance clear-cut, and patiently maintain that stance no matter what. This is what I learned through running a business.

After A Wild Sheep Chase, I continued to write with the same attitude I’d developed as a business owner. . . There’s no need to be literature’s top runner. I went on writing the kind of things I wanted to write, exactly the way I wanted to write them, and if that allowed me to make a normal living, then I couldn’t ask for more.

Thank you, Murakami. My sentiments exactly.